In infectious disease, there are a few things more satisfying than picking the perfect drug – one that targets the bug, spares the flora, and makes the pharmacist nod in approval. But every now and then, we throw the textbook at an infection… and it doesn’t budge.

The Eagle Effect, Explained

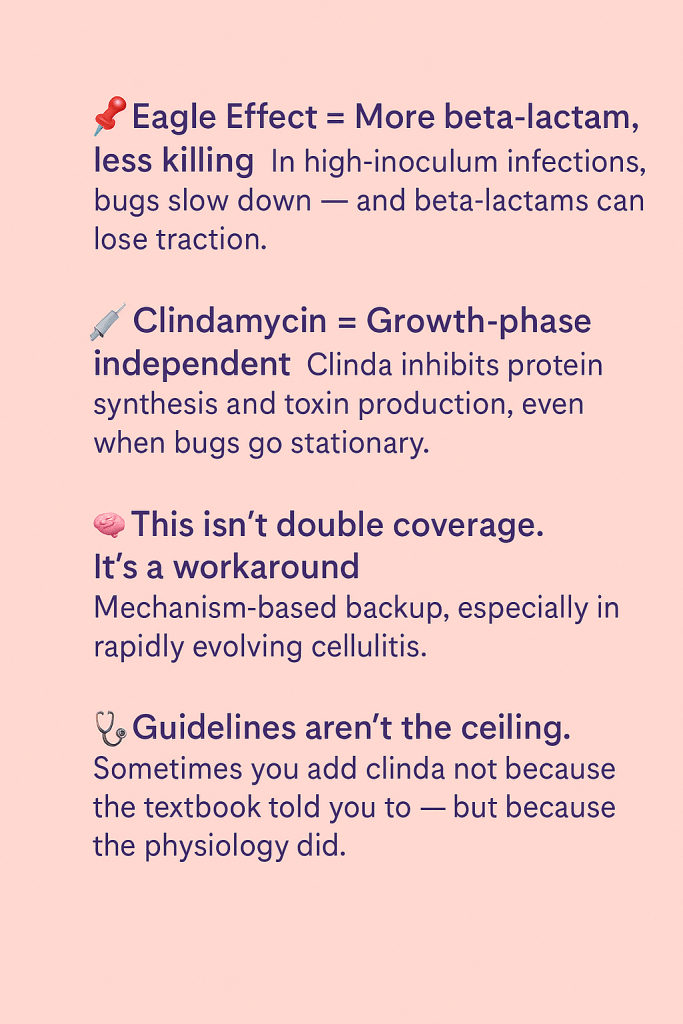

The Eagle effect is the strange-but-true observation that higher concentrations of beta-lactams can lead to less bacterial killing, especially in high-burden infections. 1 Think toxin-producing streptococcus, bulky staph infections, or – in my experience – severe cellulitis where the soft tissue looks like its negotiating surrender.

Dr. Harry Eagle first described it in 1948 when mice treated with higher-dose penicillin fared worse against Strep pyogenes.2 Since then, the Eagle effect has been confirmed in multiple models.

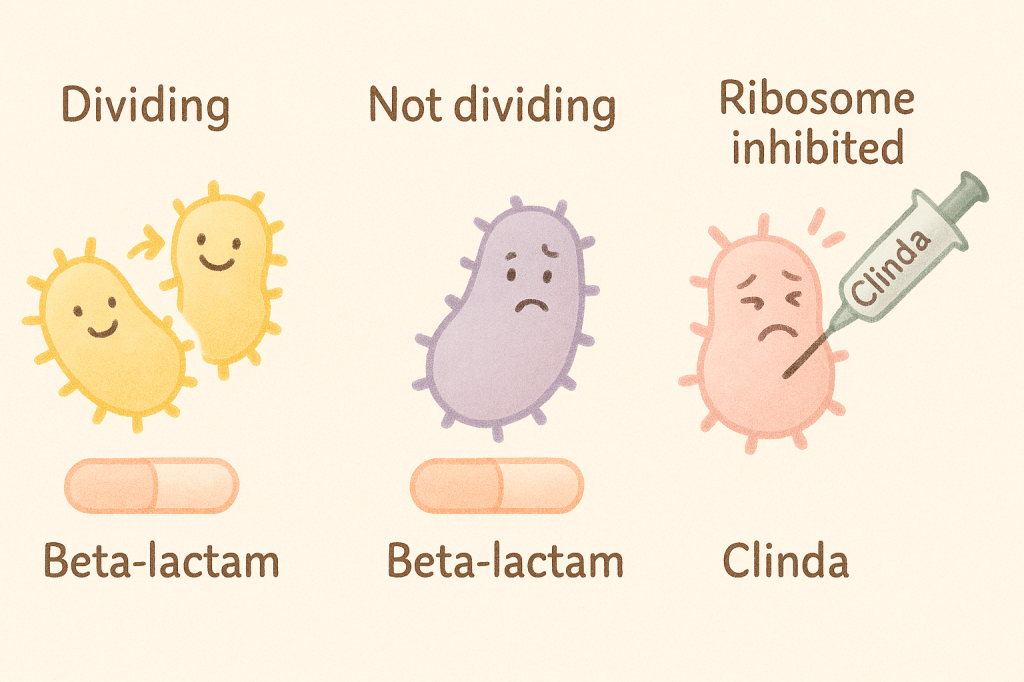

The logic? Beta-lactams rely on bacterial division. In infections with high bacterial loads, bacteria slow down or shift into stationary phase — and stop cooperating. You give more drug, and it works less.

I’ve seen this play out enough to adjust my approach. In cases of rapidly worsening cellulitis or early necrotizing fasciitis, I often pair a beta-lactam with a ribosomal inhibitor like clindamycin or linezolid. The goal isn’t to stack coverage – it’s to work around a bug that may have stopped dividing but hasn’t stopped causing trouble.

“We don’t add clinda for coverage – we add it because the bacteria might not be listening to the beta-lactam anymore.”

Clindamycin, Enter Stage Left

Ribosomal inhibitors like clindamycin don’t care if bacteria are actively dividing. Clinda binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit, shutting down protein synthesis, including exotoxins and other virulence factors that drive systemic symptoms.3 This makes clinda useful in toxin-mediated infections like nec fasc and strep TSS — and, in my experience, in rapidly progressing cellulitis that seems to be outpacing the ceftriaxone. It’s not just killing the bacteria, it’s stopping them from making things worse.

It’s not about “double coverage.” It’s about mechanism-based backup.

| Antibiotic | Target | Depends on growth | Toxin Inhibition |

| Beta-lactam | Cell wall synthesis (PBP) | Yes | No |

| Clindamycin | 50S ribosome -> protein synthesis | No | Yes |

What’s Evidence vs What’s Just Smart

Most of the data around this combo – beta-lactam + ribosomal inhibitor – comes from serious toxin-mediated infections, where clindamycin has earned its seat at the table. In necrotizing fasciitis, strep toxic shock, and invasive group A strep infections, adding clinda reduces toxin production, improves outcomes, and is formally recommended in guidelines.

For severe cellulitis? There’s less hard data. But here’s what we do have:

- High-bacterial burden can reduce beta-lactam efficacy – that’s the Eagle effect in action

- Clindamycin works regardless of growth phase. It also shuts down toxin production, which can be a silent driver behind worsening symptoms

- While most of the literature backs this combo in nec fasc and toxic shock, it’s reasonable to extrapolate the logic to severe, systemic cellulitis — especially if it’s rapidly evolving

- If there’s high bacterial burden, Eagle effect risk goes up. Clinda helps neutralize that — and buys you time.

So while we may not have a randomized trial titled “Clindamycin in Cellulitis, for People Who’ve Seen Some Things,” we do have pathophysiology, patterns, and practical outcomes that point in the same direction.

And when the leg is angry, swollen, and halfway to needing a surgical consult, I’m not waiting for a meta-analysis. I’m adding clinda.

Takeaways

- Stevens DL et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the IDSA. CID, 2014 ↩︎

- Eagle H. The Effect of Bacterial Concentration on the Lethal Action of Penicillin In Vitro. J Exp Med, 1949 ↩︎

- Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Clindamycin and the suppression of bacterial toxin synthesis. AAC, 1995 ↩︎

Leave a comment